A Good-Faith Dialogue for Wildfire Prevention

By Julio Torres Cuadros

Forestry Engineer. Member of Futuro Madera, Executive Secretary of the College of Forestry Engineers of Chile.

Dutch ethics professor Hanno Sauer argues that, to establish a constructive dialogue between two people with initially opposing positions, each must describe the other's argument in a way that the person holding that position finds satisfactory. This exercise requires avoiding reductionism, distortions, and caricatures when confronting an opposing viewpoint. The approach is not new; Isaiah Berlin long ago emphasized the need to always interpret the opposing argument in the best possible light for a good-faith dialogue.

Applying this recommendation to the wildfire prevention bill presented by the government a year ago—now under discussion in the Senate—the best interpretation we can make of the text is that its authors have prioritized, as a key factor in reducing wildfire impacts, the introduction of new mandatory planning tools for owners of vegetated land, whether native forests or plantations, especially those in wildland-urban interface zones.

According to the bill's authors, preventive actions targeting vegetation fuel would be central to a prevention strategy and thus the sole priority to address.

The Minister of Agriculture, however, disregarding the approach recommended by Sauer and Berlin, offers a reductive description of opposing arguments in his public statements, dismissing them by claiming that criticisms of the bill come from actors pushing populist positions—such as seeking financial compensation for interventions on their land (including potential plantation harvests)—and that prevention measures implemented at the owners' expense should be seen as patriotic or shared-responsibility actions.

The authority seems to imagine plantation owners as selfish, indifferent, or stingy individuals, lacking the patriotism needed to shoulder—both literally and financially—the implementation of silvicultural prevention measures deemed necessary and urgent.

The government's argument, defended by the minister, appeals to necessity but ignores arguments based on justice and efficacy, which challenge the official stance. On justice: the subjects of the bill's new requirements are not the ones causing wildfires, meaning they bear the burden for third-party actions that, it must be remembered, constitute crimes—crimes the state is constitutionally obligated to prevent or prosecute.

Wildfires in Chile are not acts of nature; there are people behind their ignition, and these individuals are not the target of this law. Thus, the bill's approach resembles the case of a pharmacy forced to close by authorities in response to repeated mass thefts by third parties. Demands are placed on the victim without proportional state action against the offenders.

Let’s not deceive ourselves: this approach does not reduce the crime—in this case, wildfires—for the simple reason that it ignores the criminal phenomenon behind them. Whether closing the pharmacy or clearing vegetation from a landowner's property, the responsibility and cost fall on the affected party.

But beyond being unjust, the measure risks being ineffective, as the law's success hinges on ensuring owners not only submit prevention plans to authorities but also execute them. These plans, drafted by professionals hired and paid by owners, must be submitted even if the property and its vegetation have no productive use.

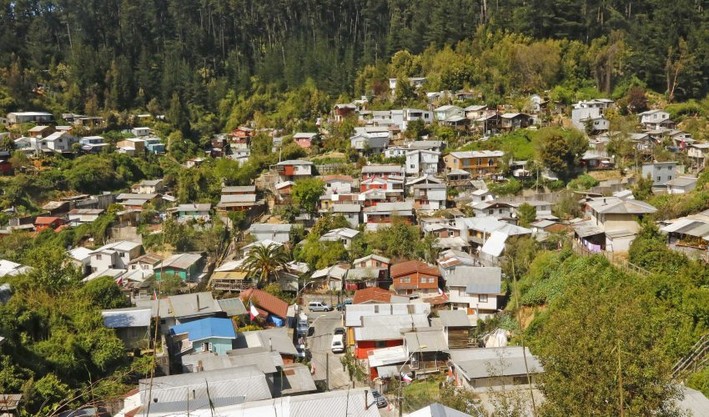

What is the expected compliance rate for these prevention plans among owners without financial support, often on unregularized land, disputed inheritances, or properties bordering squatter settlements? Does the bill address these situations? Unfortunately, it does not.

This foreshadows high non-compliance rates, leading to fines that will only make vegetation ownership in interface zones more burdensome. Could this incentivize permanently removing vegetation and repurposing the land for real estate—formally, if zoning allows, or informally through illegal occupations?

The inefficiency doesn’t end there. The National Forestry Service will also have to divert staff and resources to review, approve, and enforce prevention plans (where they exist) or penalize non-compliance, rather than deploying them for wildfire prevention.

In conclusion, the obligations imposed on owners by the bill are neither just nor likely effective—and this is not due to a lack of patriotism or empathy on their part. We can only hope the new leadership of the National Forestry Corporation receives the support needed to introduce substantive changes to a bill that, in its current form, rests on a flawed diagnosis of wildfire prevention needs—and that these changes emerge from a good-faith dialogue free of caricatured opposition.