It is already known that the Quillay (Quillaja saponaria), an endemic Chilean tree, has various uses in the pharmaceutical industry. However, this month marked a milestone in medicine as it was used in a new malaria vaccine.

On July 15, in Côte d'Ivoire, Africa, a new malaria vaccine containing Quillay was launched. In previous trials involving over 4,000 children, it achieved 75% effectiveness—the highest ever recorded for a malaria vaccine.

This antidote was developed by the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford and the Serum Institute of India. It will be administered in Africa by the pharmaceutical company Novavax, initially for infants up to 23 months old.

But why would including Quillay improve malaria vaccines? The key was tackling what could be called the "dirty secret" of vaccines by using the "saponins" from this national tree.

Why does Quillay help cure malaria?

According to an article published this week in The Telegraph, the issue with vaccines like the one for malaria was the adjuvants—chemical substances added to vaccines to enhance their immune response to an antigen.

However, for malaria, the adjuvants being used were ineffective because the parasite causing the disease, transmitted by mosquitoes, constantly changes form.

To overcome this obstacle, scientists chose to use saponin-based adjuvants, molecules found in the bark of the Quillay. Experts say these are far better at boosting the immune response of vaccines.

Saponin has different components, and the one being used for this purpose is QS-21, which is also present in shingles vaccines.

The QS-21 from Quillay is produced by grinding the tree's bark and mixing it with water to create a brown liquid. This substance then turns pasty and dries into a powder. Finally, it is combined with cholesterol and a lipid to neutralize the molecule's toxic effects.

According to pharmaceutical company GSK, which already uses this method in malaria and shingles vaccines, the QS-21-containing vaccine reduced malaria deaths by one-third.

Meanwhile, Novavax, which named its new saponin-based adjuvant Matrix-M (already approved by the World Health Organization, WHO), currently appears the most promising due to its high efficacy rate in children.

This version also uses QS-7, another saponin component more abundant in Quillay bark. Experts estimate it could halve malaria deaths.

"The R21/Matrix-M vaccine represents a paradigm shift in malaria prevention. Assuming we combine R21/Matrix-M with transmission-blocking and blood-stage vaccines, we have a real chance of cutting malaria mortality in Africa by half by the end of the decade," said Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute.

For now, it is being distributed in African countries like Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, and Sierra Leone, with plans to extend doses to Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

WHO estimates suggest at least 40 to 60 million annual doses will be needed by 2026, increasing to 80–100 million per year by 2030.

A Chilean tree against malaria—but under threat

Quillay saponin also works as an antiviral and is primarily used in soaps, earning it the nickname "soapbark tree."

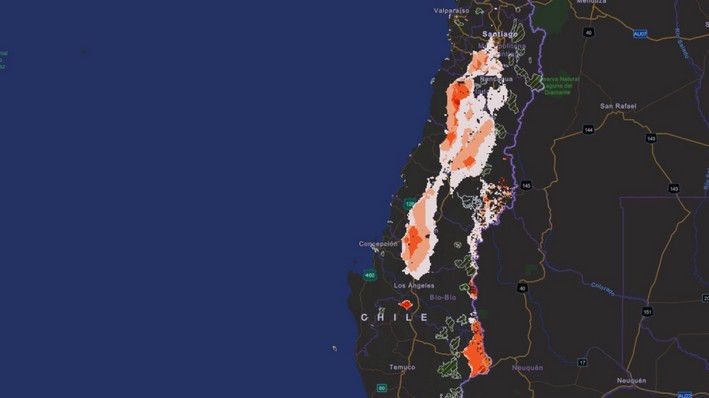

It is also used in cosmetics, shampoos, and other products. It is considered one of the most fascinating species, growing exclusively in Chile's semi-arid zone, from the Coquimbo to the Araucanía regions.

However, its usefulness also poses a threat. Quillay trees mature slowly, taking up to 25 years for their bark to be ready for saponin extraction.

This timeline clashes with the urgency of extraction. Laboratories are now attempting to accelerate the process by cloning saponins, reducing harvest time to 10 or even 5 years.

In Chile, the Quillay is a special species because it can endure conditions other trees cannot, such as nutrient-poor soils and extreme drought. Yet, evidence suggests it is reaching its limits.

According to Ladera Sur, since 2010, this tree has been affected by the megadrought plaguing Chile's arid regions. In fact, it is one of the trees losing the most greenery in pre-mountainous areas due to water scarcity.

Efforts are underway to help it persist despite these conditions, such as including it in Chile's urban tree-planting initiatives and using it for reforestation. It grows quickly and provides shade, aiding slower-growing species in surviving drought.

It is also protected by a law regulating its extraction.

Source:biobiochile.cl

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment