Congress has made progress on substantial changes to environmental governance, but it remains unclear whether the reforms will positively impact "permitology." This is the case with the new National Forestry Service (Sernafor), approved by Congress last April and already enacted by the government, which will replace the current National Forestry Corporation (Conaf).

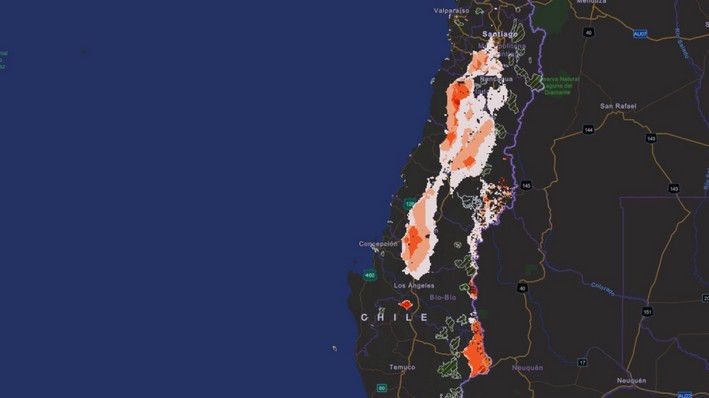

In practice, the new Sernafor will absorb about 80% of Conaf's current functions, covering wildfire prevention and the care and preservation of native forests (the remaining 20% will be taken over by the new Biodiversity and Protected Areas Service). In this role, Conaf has gained notoriety for its key involvement in complications delaying projects like the Kimal-Lo Aguirre transmission line, the rare earth development in Penco, or the Rucalhue hydroelectric plant.

However, the reform—whose implementation date must be set by presidential decree—did not innovate in this regard, keeping Sernafor as a decisive authority in "permitology." The Executive Branch claims the new framework "consolidates its role as an enforcer of sectoral laws and grants its officials the authority of notaries to verify violations."

Environmental "Permitology"

According to a comprehensive review by the National Evaluation and Productivity Commission (CNEP) on the main permits and institutions involved in the critical path of investment projects in Chile, Conaf ranks among the top three entities handling the most significant authorizations. At the same time, it has one of the highest rejection rates for reviewed projects. Between 2018 and 2022, its rejection rate was 36%, second only to the General Directorate of Civil Aviation (DGAC, with 84%) and the Ministry of National Assets (50% rejected).

Among Conaf's critical permits, the most common are those for native forest logging, xerophytic vegetation clearance (plants that grow despite water scarcity), and declarations of national interest. The latter is one of the most contested permits in the private sector, as it requires Conaf to certify when a project is of national interest, allowing exceptional intervention in protected areas.

But Conaf also plays a role in the environmental assessment stage, which occurs before processing its own permits. This was the case with the Kimal-Lo Aguirre transmission line, where the agency suggested terminating the evaluation early, arguing it "downplayed"...

A similar case occurred with the rare earth development project in Penco, where Conaf intervened in the environmental assessment process to challenge the company's proposed mitigation measures for impacts on protected species, such as the naranjillo tree.

More Efficiency?

One of the final sticking points in Congress was the actual weight of Sernafor's opinions in its reports, including those tied to environmental assessments. Sergio Donoso, president of the Association of Forestry Engineers for Native Forests—which directly participated in the technical commission that unblocked the reform—notes that the final legal wording did not alter Conaf's current prerogatives. In his view, there is no imbalance in the entity's power over investment evaluations: "Usually, major issues in permit processing stem from projects that were poorly designed or failed to consider these elements..."

Rodrigo O'Ryan, president of the Chilean Wood Corporation (Corma), highlights the positive changes introduced by Sernafor, "strengthening Conaf's historical functions while recognizing that sustainable development of the forestry and wood sector is key to the country's productive matrix and southern regional growth." However, he also notes "legitimate doubts" remain about implementing the law's objectives, though he hopes the new service will "resolve current bottlenecks, like lengthy approval times for management plans, which hinder sustainable native forest management—essential for reducing wildfires, enhancing carbon capture, and boosting local economies."

Source:El Mercurio

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment