Chile’s Mediterranean forest, a unique ecosystem in South America and a key player in the country’s water and climate regulation, is under threat. A recent study published in the journal Science of the Total Environment warns that nearly 40% of Mediterranean sclerophyllous forests are at high or very high risk of collapse due to the combined effects of climate change, wildfires, soil degradation, and agricultural and forestry expansion.

In the Biobío Region, where this type of forest coexists with emblematic species such as quillay, peumo, and boldo, the situation is especially concerning. Prolonged droughts over the last decade are compounded by the expansion of exotic species plantations, which displace native forests and increase their vulnerability to fire.

Findings

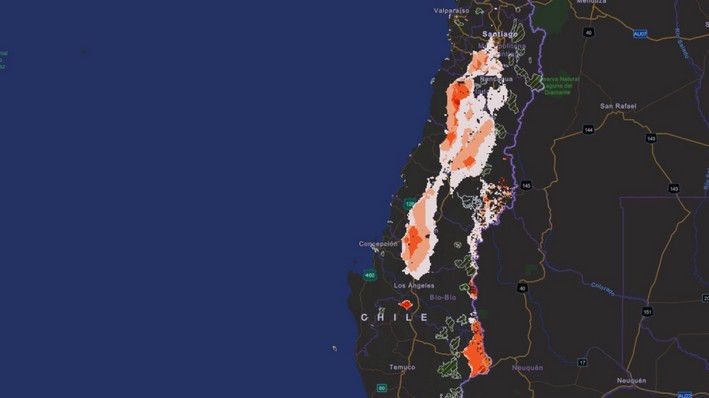

The analysis was conducted by a team of Chilean and international researchers, who applied a multifactorial risk index based on climate, productivity, habitat fragmentation, and land use variables. The result: 39.8% of the country’s Mediterranean forest stands are at critical risk.

In more than 90% of cases, a loss of vigor was detected, meaning trees have reduced their ability to grow and produce biomass. Although the most critical areas are concentrated in the central zone (between Valparaíso and O’Higgins), the study warns that in Biobío, drought conditions and forestry pressure are pushing the ecosystem toward a point of no return.

The value of the Mediterranean forest in Biobío

Although Biobío is known for its 597,000 hectares of native forests, where oak, raulí, coihue, and araucaria predominate, the Mediterranean forest plays a key role in

These forests regulate water, prevent erosion, capture carbon, and act as natural barriers against fires. However, they are also the most pressured by human activity: historically, large parts of their area have been replaced by agricultural, urban, or forestry expansion, drastically reducing ecological connectivity.

Nonguén National Park, just a few kilometers from downtown Concepción, is an example of the last protected Mediterranean remnants in the region. Threatened species such as the queule (Gomortega keule), one of the rarest and most valuable trees on the planet, and several raptors under conservation categories survive there.

Fire and drought: the close enemies

The last wildfire season was the most devastating in a decade: over 50,000 hectares of vegetation were consumed by fire in the region. Although much of it was forestry plantations, remnants of Mediterranean and sclerophyllous forests were also severely affected.

Dr. Cristián Echeverría, director of the Landscape Ecology Laboratory at the University of Concepción, warns that “These ecosystems have been subjected to land use change over recent decades due to agricultural, forestry, and urban expansion. When combined with droughts and fires, the impact is significant. Mediterranean forests are highly exposed because they are often located near large urban centers, with greater human pressure.”

“More temperate forests are accustomed to a different rainfall regime, and at the same time, these Mediterranean forests are always associated with proximity to large urban populations, which subjects them to more human pressure,” the academic noted.

Professor Marcela Bustamante, an academic at the Faculty of Forest Sciences of the University of Concepción, explains why this ecosystem is so unique: “Sclerophyllous forests have developed unique adaptations to drought, such as hard leaves, deep roots, and the ability to resprout after fires. But these same characteristics do not make them invulnerable: when disturbances occur intensely and frequently, resilience is lost. In that scenario, the system can turn into shrubland or grassland, and restoring an original forest becomes nearly impossible.”

From an institutional perspective, the Biobío Regional Minister of the Environment, Pablo Pinto, acknowledges the severity of the diagnosis and assures that measures are being taken: “We are working on the Regional Climate Change Plan, with reforestation actions, landscape-scale restoration, and protection of watershed headwaters. This study is a call to action: if we don’t act now, we risk losing a natural heritage that is fundamental to the lives of local communities.”

A global hotspot under pressure

The Chilean Mediterranean forest is part of the “Chilean Winter Rainfall–Valdivian Forests” biodiversity hotspot, recognized globally for its concentration of endemic species and high level of threat. It is home to unique species such as the Chilean palm (Jubaea chilensis), the queule, and the southern belloto, all in concerning conservation status.

Bustamante emphasizes that “Mediterranean Chile is the most threatened and irreplaceable core of the hotspot. It harbors lineages of great evolutionary uniqueness and provides strategic ecosystem services: it regulates water for cities and fields, controls erosion, and contributes to adaptation to climate change. Losing it would mean losing a natural shield.”

An urgent call

The study published in Science of the Total Environment concludes that, without urgent protection and restoration measures, Chilean Mediterranean forests, including those in Biobío, could enter an irreversible phase of degradation.

The threat is compound and synergistic: increasingly frequent fires, prolonged droughts, habitat fragmentation, and soil degradation interact in a cascading manner, reducing the system’s recovery capacity.

Source:Diario Concepción

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment